Od 2000. godine, produktivnost resursa gotovo da nije bila namerni stub ekonomskog rasta EU. Ako ništa drugo, bila je naknadna misao. Pa ipak, gotovo slučajno, produktivnost resursa EU je kumulativno porasla za oko 52% do 2024. godine. Ne zbog smelog strateškog pomeranja, već uglavnom zato što su krize primorale ekonomiju da se ponaša drugačije. Najveći dobici su se dogodili tokom i nakon globalne finansijske krize (2007-2008) i, u manjoj meri, tokom pandemije COVID-19 – perioda kada je BDP rastao brže od domaće potrošnje materijala, ne zato što je EU to tako planirala, već zato što je potrošnja padala brže od proizvodnje.

Ironično, globalna finansijska kriza se pokazala kao jedna od najefikasnijih „politika efikasnog korišćenja resursa“ EU. Produktivnost resursa je porasla kako se ekonomska aktivnost oporavljala, dok je korišćenje materijala ostalo prigušeno. COVID-19 je nakratko prekinuo ovaj trend, uzrokujući umeren pad, ali čak i tada je pad produktivnosti resursa bio daleko manji od smanjenja BDP-a između 2019. i 2020. godine. U postpandemijskom oporavku (2021-2024), obrazac je postao još jasniji: BDP EU je porastao za oko 5%, dok je domaća potrošnja materijala pala za više od 7%. Razdvajanje se konačno dogodilo – ne namerno, već okolnostima.

Pažljiviji pogled na dve komponente produktivnosti resursa, BDP i domaću potrošnju materijala (DMP), objašnjava zašto. Do 2007. godine, obe su rasle gotovo paralelno, održavajući produktivnost resursa uglavnom ravnom. Između 2008. i 2016. godine, one su se naglo razišle, krećući se u suprotnim smerovima. Od 2016. do 2021. godine, ponovo su se približile, prateći slične godišnje obrasce. Tek posle 2021. godine došlo je do snažnog razdvajanja – upravo kada je EU počela ozbiljnije da govori o održivosti, nakon što je od nje nenamerno imala koristi više od decenije.

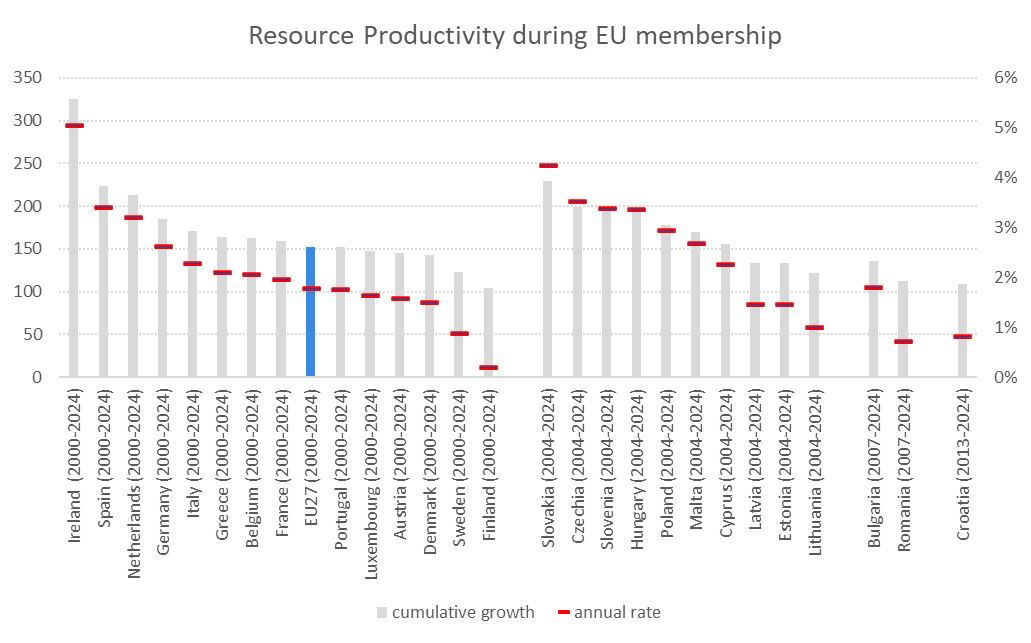

Na nivou zemalja, ironija se produbljuje. Produktivnost resursa povećana je u skoro svim državama članicama EU između 2000. i 2024. godine, ali najveći dobici nisu došli iz najvećih ili najrazvijenijih ekonomija EU. Nemačka, Francuska i Italija nisu predvodile ovu transformaciju. Umesto toga, najveći porast je zabeležen u Irskoj, Španiji, Slovačkoj, Češkoj, Sloveniji i Holandiji, gde se produktivnost resursa više nego udvostručila. Čak i tokom recesije izazvane COVID-19, zemlje poput Irske, Mađarske, Malte i Slovačke nastavile su da poboljšavaju svoje odnose.

Povećanje produktivnosti resursa omogućava ekonomski rast uz smanjenje pritiska na životnu sredinu – udžbenička definicija razdvajanja. Međutim, u praksi, veliki deo „uspeha“ EU odražava strukturne promene, a ne čuda efikasnosti. Proizvodnja koja koristi materijale sve više se premeštala iz centralnih ekonomija (Nemačka, Francuska, Italija) u novije države članice (Slovačka, Češka, Mađarska). Centralna ekonomija troši manje materijala kod kuće – ne zato što koristi manje resursa na globalnom nivou, već zato što ih koristi negde drugde.

Ukratko, EU je poboljšala produktivnost resursa – ali uglavnom bez pokušaja, i često pomeranjem problema umesto njegovim rešavanjem.

Izvor: EUROSTAT

Since 2000, resource productivity has hardly been a deliberate pillar of EU economic growth. If anything, it has been an afterthought. Yet, almost by accident, EU resource productivity increased cumulatively by around 52% by 2024. Not because of a bold strategic shift, but largely because crises forced the economy to behave differently. The strongest gains occurred during and after the global financial crisis (2007-2008) and, to a lesser extent, during the COVID-19 pandemic – periods when GDP grew faster than domestic material consumption, not because the EU planned it that way, but because consumption collapsed faster than output.

Ironically, the global financial crisis proved to be one of the EU’s most effective “resource efficiency policies”. Resource productivity surged as economic activity recovered while material use remained subdued. COVID-19 briefly interrupted this trend, causing a moderate decline, but even then the fall in resource productivity was far smaller than the contraction in GDP between 2019 and 2020. In the post-pandemic recovery (2021-2024), the pattern became even clearer: EU GDP grew by around 5%, while domestic material consumption fell by more than 7%. Decoupling finally happened – not by design, but by circumstance.

A closer look at the two components of resource productivity, GDP and domestic material consumption (DMC), explains why. Until 2007, both grew almost in parallel, keeping resource productivity largely flat. Between 2008 and 2016, they diverged sharply, moving in opposite directions. From 2016 to 2021, they converged again, following similar annual patterns. Only after 2021 did a strong decoupling emerge – precisely when the EU began talking more seriously about sustainability, after having benefited from it unintentionally for over a decade.

At the country level, the irony deepens. Resource productivity increased in almost all EU Member States between 2000 and 2024, but the strongest gains did not come from the EU’s largest or most advanced economies. Germany, France and Italy did not lead this transformation. Instead, the biggest increases were recorded in Ireland, Spain, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Slovenia and the Netherlands, where resource productivity more than doubled. Even during the COVID-19 recession, countries such as Ireland, Hungary, Malta and Slovakia continued to improve their ratios.

Increasing resource productivity makes it possible to grow economically while reducing environmental pressure – the textbook definition of decoupling. In practice, however, much of the EU’s “success” reflects structural shifts rather than efficiency miracles. Material-intensive production was increasingly relocated from core economies (Germany, France, Italy) to newer Member States (Slovakia, Czech Republic, Hungary). The core consumes less material at home – not because it uses fewer resources globally, but because it uses them elsewhere.

In short, the EU improved resource productivity – but mostly without trying, and often by moving the problem rather than solving it.

Source: EUROSTAT